By Justin Wilmes, East Carolina University

“Nemtsov’s murder was the final chord in the period of building a democratic society in Russia, which was born in 1991 during the putsch, and to which all of our hopes were tied. It placed a period at the end of this part of Russian history. To me, it means that Russia needs a new direction, a new history.”

-Vitalii Mansky[i]

The assassination of a prominent politician is a shocking event, carrying in it a kernel of the uncanny that disturbs and disorients a society. The assassination on February 27, 2015 of Boris Nemtsov, the former Deputy Prime Minister of Russia and heir apparent to Boris Yeltsin in the late 1990s, sent shockwaves across Russia and around the world. Although Nemtsov was but one of many victims of repression in Russia in recent years—names like Anna Politkovskaya, Sergei Magnitsky, Mikhail Khodorkovsky, Alexei Navalny, and the members of Pussy Riot are but the most prominent—he was the highest profile politician to be assassinated in decades, and his death had a resonance not seen previously. It prompted an outpouring of grief and anger at a memorial march two days later, where tens of thousands turned out to honor Nemtsov’s memory and protest the authoritarian abuses of the current government.

Figure 1: The Memorial March two days after Nemtsov’s Death, March 1, 2015

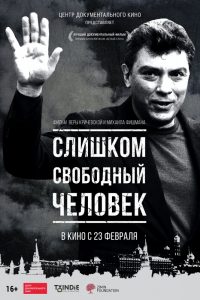

In the realm of cinema, Nemtsov’s life and death inspired three new documentaries in 2016. While overlapping somewhat in their narratives and use of archival footage, these three films provide rather different and complementary points of view that bring the larger picture of Nemtsov’s life—and post-Soviet society writ large—into focus. Zosya Rodkevich’s highly personal My Friend, Boris Nemtsov provides insight into Nemtsov the man in his most everyday and unscripted moments. Vladimir Kara-Murza’s Nemtsov sheds light in particular on the prehistory of Nemtsov’s career as a physicist and governor of Nizhny Novgorod, before his meteoritic rise in national politics. The clear pièce de résistance is Vera Krichevskaia and Mikhail Fishman’s The Man Who Was Too Free, which not only provides a rich portrait of Nemtsov’s life, but distills a remarkably insightful narrative about Russian society over the last quarter century. As one Russian critic put it, the film manages “to show precisely which moments in post-Soviet history were key for the Russia in which we now live; due to precisely which actors and which decisions.”[ii] With more extensive resources and budget, The Man boasts crisp production and interviews with many of the biggest players in Russian politics, such as Tatyana Yumasheva, Mikhail Khodorkhovsky, and Alexei Navalny. While all three films are thematically and aesthetically interesting, The Man Who Was Too Free is one of the best Russian documentaries in recent years, providing a rare degree of clarity about post-Soviet society and politics.

Of the three, only The Man Who Was Too Free will have a meaningful circulation in Russian theaters following its recent release on February 23. The others have been screened only at special events and festivals. For interested viewers, The Man Who Was Too Free will be available online in April 2017 for purchase and streaming via iTunes.

Nemtsov and ‘the Russia We Lost’

The story of Nemtsov is essentially the story of Russia’s quarter-century period of fledgling democracy. When Gorbachev first spoke of perestroika and glasnost’ in 1985-86, Nemtsov was a 26-year-old doctoral student of physics in Gorky (today Nizhny Novgorod). He made his foray into civic life in 1988 when, not long after the Chernobyl disaster, he led a successful campaign to prevent the construction of a large nuclear plant in his city. As a wave of civic activism swept across Russia, Nemtsov put his promising academic career on hold and was elected to the Congress of People’s Deputies in 1990. He was governor of Nizhny Novgorod from 1991-1997, managing shortages of food and goods, staggering inflation, and other crises with relative success. As a symbol of a new politics of openness and transparency, Nemtsov was a rising star and a political asset, and in 1997 Yeltsin and company convinced him to leave Nizhny to become Deputy Prime Minister in order to right the ship of their administration. Many believe that, had Nemtsov remained in Novgorod, he would have become President, leaving us to wonder what kind of Russia we might have had today.

As all three of these films make abundantly clear, Nemtsov was indeed ‘too free’ for his time and place. His unwillingness to compromise put him at odds with the power establishment on countless occasions. In 1995, as Yeltsin’s close confidante and appointee for governor, Nemtsov defied his ‘benefactor’ by gathering one million signatures—literally—to demand the end of the First Chechen War. In response, Yeltsin would stonewall Nemtsov for months, before suddenly calling him and asking him to go to Chechnya with him to end the war.

Another telling episode featured in these documentaries: It’s 1997 and Yeltsin’s administration is increasingly under the control of the oligarchs (to whose backing they owe their re-election). Boris Berezovsky is the head of Yeltsin’s security council and Boris Nemtsov is his Deputy Prime Minister. Unwilling to ignore Berezovsky’s corrupt dealings, Nemtsov goes to Yeltsin with an ultimatum—either Berezovsky is fired or he resigns. Yeltsin sides with Nemtsov and fires Berezovsky. Although he won that battle, he lost the war. Around this time, he spearheaded the effort to clean up the privatization process and implement bona fide auctions for state assets, in place of the highly orchestrated ones that occurred previously. Almost single-handedly, going against the grain, Nemtsov would prevent the acquisition of the Soviet media conglomerate Svyazinvest by oligarchs Berezovsky and Gusinsky. He would pay dearly for this principled stance, enduring a smear campaign in the media—by ORT and NTV, channels owned at the time respectively by Berezovsky and Gusinsky—for the next two years that caused his political ratings to plummet. In another ‘what-if’ scenario, The Man Who Was Too Free suggests that had Nemtsov simply cooperated in the Svyazinvest deal, he would have been Russia’s next president. Thus he was not only one of post-Soviet Russia’s first genuine reformers, he was one of the first victims of its postmodern media wars.

Nemtsov was an ambivalent supporter of Vladimir Putin’s election in 2000, taking a wait-and-see approach and meeting with him frequently as a representative of the—then still ‘systemic’—opposition. His disarming sense of humor and charisma afforded him a friendly and intimate audience with the young Putin (speaking in the informal Russian ‘ty’) for a time. But as Putin revealed his authoritarian proclivities, Nemtsov began to speak out openly against him. He was quickly marginalized and became a leader of the non-systemic opposition (nesystemnaia opozitsiia). Nemtsov ultimately became a key, many say the key, leader of the opposition in the post-2012 years for his ability to unite its fractious groups—from the youthful Navalny movement, to Parnas and other opposition parties, to intelligentsia members like Boris Akunin—bringing them together for the Bolotnaya protests in 2011, Navalny sentencing protest in 2013, and other mass protests. In his final years, Nemtsov endured numerous arrests and detentions, threats, and physical attacks before his tragic death in February 2015, a day that many feel signified, not only the death of a man, but of an entire period in Russian history.

The Man Who Was Too Free (Fishman and Krichevskaya, 2016)

The Man Who Was Too Free is a crisp and minimalistic production, with relatively few aesthetic flourishes. Its strength lies in its remarkable historical scope. Divided into over twenty episodes from Nemtsov’s life—“Summer 1994,” “War on the Oligarchs 1997,” etc.—intertitles structure the film and are accompanied by a cardiogrammed heartbeat, evoking the precarity of his life. The film and its commentators make clear: Nemtsov was an anomaly, an unassailably honest and principled actor amidst the snake-pit of post-Soviet politics. Several journalists, who had run kompromat (smear segments) about Nemtsov in the past, express regret and unequivocal respect for him. Commentators in all three films point out that, try as they might, his political enemies could not pin any sort of real corruption on him. It is telling that the most remembered scandal in Nemtsov’s career was the infamous ‘white pants’ episode, when he showed up wearing white khakis to a meeting with Gaidar Aliyev, then President of Azerbaijan, breaking dress code protocols (surely a sign of elitist exceptionalism!). Rather, Nemtsov’s political opponents relied on vague, uninformed associations of him with the corruption and privatization of the Yeltsin years, despite the fact that he was the most principled actor among all the reformers, and often broke rank with them.

The Man is nuanced and thoughtful, cutting across ideological orthodoxies and posing interesting questions. Interviewee Mikhail Fridman, for instance, provocatively asks, “Maybe it would have been better if the Communists had won the 1996 presidential election? From the point of view of historical process, it’s entirely possible that the country would have been better off. We would have created a precedent of real elections where an opposition would come to power.” Navalny and other opposition leaders admit candidly that they kept some public distance from Nemtsov, despite their tremendous regard for him, because of his associations with the troubled 1990s.

Figure 2: Closing scene of The Man Who Was Too Free

The film’s closing scene is one of its most memorable and poignant. Nemtsov is depicted in slow-motion, walking along an evening street, chest puffed out proudly and a giant smile on his face. After all of the betrayals and dangers he encountered in his life as political reformer, there he is at the end: unafraid, defiant, free. Nemtsov’s voiceover concludes the film and seems to carry with us beyond the closing credits: “People who fought for freedom—the Decembrists, their followers and now us—they played a very important role in the life of Russia, but they were always the minority. They always moved the country forward, often paying with their lives, as it was with Alexander II, Stolypin, Gorbachev and Yeltsin (who weren’t killed physically, but morally). But, I will return. Don’t you worry, I’ll be back.”

My Friend, Boris Nemtsov (Zosya Rodkevich, 2016)

Neither a comprehensive biopic nor a taut exposition like the other two documentaries, Rodkevich’s My Friend, Boris captures lyrical fragments of Nemtsov’s life. In close—often uncomfortably close—shots, the viewer is privy to the man behind the political persona, his ribald humor, his warmth and exuberance, his uncensored and witty barbs. In one scene, he memorably describes Putin as ‘a C-student (troishnik) who got a bunch of power.’ A touching and vaguely flirtatious friendship evolves between him and the young filmmaker Rodkevich. With handheld camera and footage unadorned by music or extensive editing, Rodkevich’s film achieves an authenticity typical of Marina Razbezhkina’s documentary school.

Figure 3: Scene from Rodkevich’s My Friend, Boris Nemtsov

Often bawdy and unfiltered, Nemtsov is shown invariably cutting up with journalists, political allies and opponents. In a televised debate against an LDPR politician, Nemtsov tells him ‘You look fresher than Zhirinovsky!’ In a somber courtroom during the Navalny trial, he makes jokes with journalists about a real Russian village called Bzdili (‘fart village’). We see him at the front of the marches, chanting ‘Russia Without Putin!’, being arrested, and we are privy to some of his penetrating insights in private conversations: ‘Let’s be honest. It is a better life now [under Putin]. But more disgusting. That’s the truth. A huge amount of people…put a period after the word ‘better.’ Those are supporters of Putin. And only the middle classes place the stress on the phrase ‘more disgusting.’’ Though roughly edited and structured—intentionally it seems—My Friend, Boris Nemtsov is indeed a wonderful complement to The Man, offering a gritty authenticity smoothed out by the former.

Nemtsov (Vladimir Kara-Murza, 2016)

Vladimir Kara-Murza’s Nemtsov is perhaps most remarkable for its context. After working closely with Nemtsov in politics for many years, Kara-Murza commemorates his friend and colleague in his own documentary. I corresponded with director Kara-Murza in January 2017 and he generously shared his film with me. To my shock, one week later I read that Kara-Murza had fallen into a coma after allegedly being poisoned.[iii] The grim irony is plain enough—having just made a documentary about an opposition leader’s assassination, an attempt was made on Kara-Murza’s life. Thankfully, as of this writing, Kara-Murza has partially recovered and since fled Russia. His courage in the face of threats and political pressure, like that of Nemtsov, is inspiring.

Though more modest in scope than Krichevskaya and Fishman’s documentary, Nemtsov, is a thoughtful document of Nemtsov’s life, which fills in some gaps left by the other films—about Nemtsov’s early life in Gorky, among other things. We learn of the final period in Nemtsov’s life in which he resurrected his political career on the local level, winning election to the regional Duma in Yaroslavl in 2013. Canvasing the entire city on foot, speaking with old women, laborers, and residents, Nemtsov stubbornly advocated the same simple political program he had articulated in his first campaign 25 years earlier: no lying, no stealing, and real elections. This message lives on today through Nemtsov’s memory and the opposition movement that he fought for years to galvanize.

[i] http://ru.hromadske.ua/ru/articles/show/ne_bylo_by_etoj_vojny_esli_by_ee_ne_podogreli

[ii] https://meduza.io/feature/2017/02/07/samyy-svobodnyy-chelovek-o-chem-my-uznali-iz-kinobiografii-borisa-nemtsova

[iii] https://www.nytimes.com/2017/02/06/world/europe/russia-vladimir-kara-murza-putin.html

Justin Wilmes is Assistant Professor of Russian at East Carolina University. He graduated from Miami with a BA in Russian and BS in Computer Science and then earned his PhD from The Ohio State University.